- Posted On:2023-06-21 18:06

-

1019 Views

US doctors are rationing lifesaving cancer drugs amid dire shortage

For cancer patients in the US right now, a horrifying reality may follow the devastating diagnosis—their malignant disease may go undertreated or even untreated.

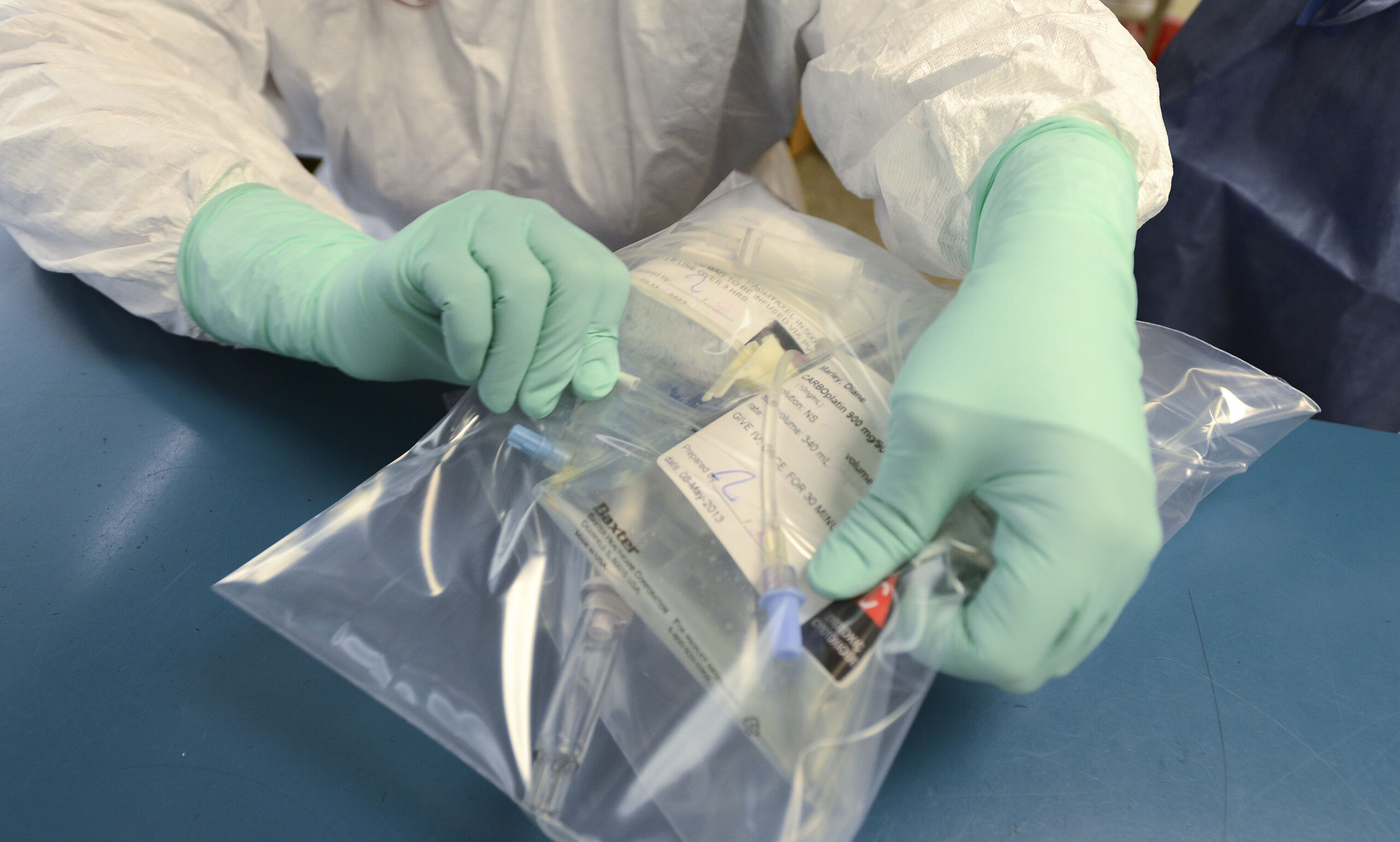

The country is in the grips of a dire shortage of cheap, generic platinum-based cancer drugs used to treat various cancers in hundreds of thousands of US patients each year—patients with lung, breast, bladder, ovarian, testicular, endometrial, and head and neck cancers, and others.

Despite being in one of the wealthiest countries in the world, US doctors are being forced to ration the cisplatin and carboplatin drugs. That means prioritizing cancer patients who have a shot at being cured over patients at later stages, in whom the drugs may simply slow progression and buy time. Still, those with curable cancers may not get a full dose; some may only have 80 percent or 60 percent of standard doses available to them. And doctors don't know how these partial doses will affect patient outcomes.

In an opinion piece for Stat News this week, San Diego-based oncologist Kristen Rice described the dilemma faced in caring for just one of her patients, one with a curable lung cancer that is slightly too large to be surgically removed. Normally, the plan would be three cycles of platinum-based drugs, and if the cancer shrinks a bit, they can go in for surgery. But "if we reduce her doses to extend our drug supply, we risk reducing the chance of response, and that could mean missing a chance at potentially curative surgery," Rice wrote. "If her scan after that third cycle isn’t what we hope, the first question she will ask is: 'What if I had received the full dose? Would it have made a difference?'"

Meanwhile, in Fredericksburg, Virginia, oncologist Bonny Moore told KFF Health News that clinicians at her practice had given some uterine cancer patients 60 percent doses of carboplatin last month before shifting to 80 percent doses when a small shipment came in. On June 2, they were glued to their drug distributor's website, hoping for the drug to come back in stock. It did not. Doses stayed at 80 percent.

On Tuesday in Alaska, Melissa Hardesty, a gynecologic oncologist at Alaska Women’s Cancer Care in Anchorage, told Alaska Public Media that her clinic is also rationing drugs. "Right now, as of today, this second, I have no cisplatin in-house," said Hardesty. "So if I have a new cervix cancer patient show up, I’m essentially going to be extrapolating from other things to treat that person." That means, she explained, using other types of cancer-fighting drugs and hoping they work on the cancers her patients have. This may or may not work. And alternative treatments can have more severe side effects.

A plant with problems

The situation is made yet more desperate because the shortage isn't expected to end quickly, and even if the most immediate problems are solved, the long-term foundational cracks in the generic drug industry will likely remain.

The current shortage was triggered late last year when the Food and Drug Administration inspected a drug manufacturing facility owned by Intas Pharmaceuticals in Ahmedabad, India. Inspectors found egregious violations. Afterward, Intas voluntarily shut down the facility, which had supplied around half of the generic cisplatin and carboplatin in the US.

The stunning inspection report, released in January, leaves no doubt as to why the plant was shut down. In addition to various manufacturing violations, including laboratory and quality control problems, inspectors reported finding a truck 150 meters from the facility loaded with plastic bags full of shredded and torn documents. When the inspector dug into the documents, they realized they were quality-control documents and analytical weight slips.

In another instance, the inspection report notes that an employee, upon learning the FDA inspectors were walking through the quality-control lab, ran to the balance room and "immediately rushed and tore apart balance printouts along with Auto Titrator spectrums and threw the torn pieces into the small trash container located next to the balance. Later, he threw [redacted] acid solution inside the same trash in an attempt to destroy the evidence." The bag of torn, acid-soaked reports was later found stuffed under a staircase.

The FDA has since tried working with other manufacturers to boost production of the cancer drugs and is exploring temporarily importing drugs from China to ease the shortage. But many generic drug facilities already work at capacity, making a boost in production difficult to impossible. It's also unclear how much the imported drugs will help.

Long-term problems

Richard Pazdur, director of the FDA Oncology Center of Excellence and acting director of the Office of Oncologic Diseases, told The Cancer Letter that the FDA has limited power to help in situations like this.

"We cannot require a company to make greater quantities of the drug—specifically, to step up production," he said. "In addition, FDA cannot require that essential drugs, such as cancer therapeutics, have diversified supply chains such that there is not overreliance on a single facility or country for an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) or key starting materials."

In general, the root causes of drug shortages are well-established. Most shortages involve low-cost, off-patent generic drugs, which have profit margins that are razor-thin to non-existent. This is driven by middlemen who have, in recent years, pushed down wholesale prices to rock-bottom levels, to the point that the generics industry often loses money on drugs. This disincentivizes pharmaceutical companies from helping to make much-needed generic drugs and creates fragile supply chains. As KFF notes, several generic makers have recently filed for bankruptcy.

In contrast to this is the reality that the federal government is funding the development of new "moonshot" cancer treatments—new treatments that are almost always expensive, sometimes tens of thousands of dollars per year. Cisplatin, meanwhile, costs as little as $6 a dose.

Mark Ratain, a cancer doctor and pharmacologist at the University of Chicago, told KFF the situation is "insane. … Your roof is caving in, but you want to build a basketball court in the backyard because your wife is pregnant with twin boys and you want them to be NBA stars when they grow up?”

While experts toss out ideas for long-term solutions—like tax incentives, subsidies to start up domestic production, and renegotiating drug prices that the federal government pays—it's unclear when any such fixes will come into play or even when the immediate shortage will end. In addition to cisplatin and carboplatin shortages, there are around a dozen other cancer drugs in short supply and yet more with looming shortages, Rice, the oncologist in San Diego, wrote:

"I honestly don’t understand why patients are not rioting in the streets about this."